True and Fascinating Canadian History

The Mystery Of The Constable

Whose Confession Came Too Late

by J. J. Healy

In liberal democratic countries such as the United States, Great Britain, Australia and Canada there are striking similarities in the drafting and composition of laws as well as their administration in and by the courts. In these countries and others too, certain crimes are so serious that they simply go against all societal values; murder, theft, assaults of all kinds, frauds, robbery and so on.

Yet, in spite of the seriousness of these offences, there can be distinct differences in the penalties set by the courts depending on the province or state. Consider, for instance, that Canada abolished the death penalty in the mid 1970's yet convicted persons can still be executed today in some American states.

The story which follows is about a constable who was charged with a serious crime. As time went on, he appeared before the courts. He pleaded not guilty and some observers agreed that he was innocent. Others said that he was guilty. But, nevertheless, the case took an interesting twist which revolved around the raw nature of his confession. As the story unfolds, one may want to consider if telling the truth simply complicates the entire judicial process. There may be a lesson or two for all of us in 'The Mystery of the Constable Whose Confession Came too Late'.

Down through time, the notion of telling the truth has always been an imperative and known to every society. Truth is first and foremost the brick upon which all democratic institutions rely; the family, the courts, business dealings of all kinds and relationships between friends. All transactions, the world over, depend on people telling the truth and there is little doubt that society would collapse if the situation were otherwise.

Within the family unit, parents emphasize to their children the importance of telling the truth and its value can easily be extended and compared to expectations in court. Suppose, for instance that a child broke a window with a baseball. Other siblings act as witnesses. Parents mull over the sincerity of the child’s confession, if such be the case, as well as the circumstances. Some trepidation among the children might be expected before punishment is announced. An appeal is usually futile. Many, many years later one can still recall these childhood events, the scene with parents and whether or not the punishment was worthy.

In court, essentially the same scene is replayed. The police and others act as primary witnesses. The judge sits on an elevated platform and the accused has an opportunity to explain his or her actions. The court room is filled with an electric sense of anticipation of what is to follow. The judge weighs the evidence, delivers a lay sermon to the accused and sentence is passed. The case with the child and the trial of an adult very often hinges on trust – is the person a credible witness – did he or she tell the truth? The whole point about whether or not one is believed became very apparent in the ‘Mystery of the Constable Whose Confession Came Too Late’.

No one seems to know exactly where William Pepo was born, but it was sometime around 1861 and apparently he had once been in the German Army. He joined the North West Mounted Police as Reg.#1917, a constable in April, 1887 and his career was measured in a few short months. He went on to serve in the Calgary, AB area, but by December Pepo was already in court. He was charged with stealing some cigars from a saloon and, upon conviction, he was ordered dismissed from the NWMP. For sure, his reputation had become sullied.

Shortly after his court appearance and his dismissal from the Force, Pepo met a friend by the name of Julius Plath and the two crossed the border and wandered into nearby Helena, Montana, US.

According to newspaper accounts, it wasn’t long before Julius Plath was reported as a missing person. The two had been spotted together so Pepo became the principle suspect in the disappearance of Plath. But, Pepo evaded authorities who wanted him for questioning. Then his trail went as cold as a February frost.

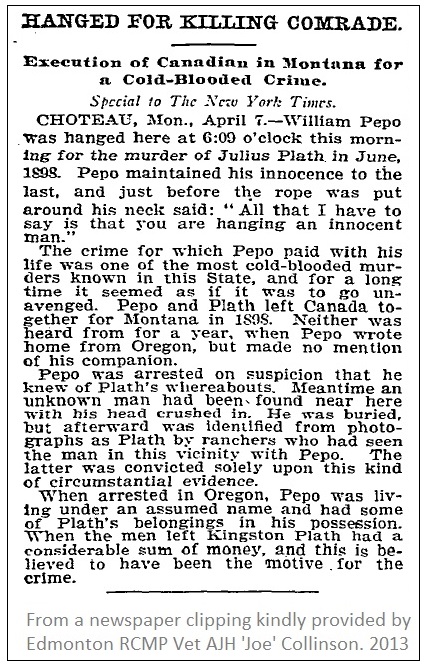

In the subsequent months, Pepo wrote to his family living in Canada and his address was traced to Oregon State where he had been living under an assumed name. At about the same time, Julius Plath’s body was found in Montana. By the looks of his crushed skull, police had no trouble announcing that Plath had been murdered.

Pepo was soon arrested in Oregon as a suspect in the disappearance of his deceased friend and he was returned to Montana to stand trial for the murder of Julius Plath. He strongly claimed his innocence, but at the time, the evidence against Pepo looked overwhelming. By all accounts, Plath had carried a considerable sum of money with him when he left Canada. Other witnesses came forward and also testified against Pepo.

In court, some farmers testified that they had seen Pepo with the victim prior to the murder. As well, some personal clothes were found at the crime scene and another main witness, Reg.#626, NWMP Constable Bertles identified the personal belongings as those of Pepo’s.

Pepo denied any knowledge of the murder or of inflicting any harm on the victim, or having any knowledge about Plath's money. But in the eyes of the court his clothes were enough to put Pepo in close proximity to the victim and the murder scene. Robbery was said to have been the motive for Plath’s murder. At trial, the court set aside Pepo’s claim of innocence. Whatever he had said by way of a half-hearted confession was not believed. He was found guilty of murder.

Still, according to all reports, it is worthwhile to note that the evidence against Pepo was mostly circumstantial; first, Plath was known to be in possession of some money, but his money was never found. Next, Pepo had been seen with Plath, but there were no eye witnesses to the actual assault upon Plath's head and his murder. Yet, Pepo had moved quickly and quietly out of Montana and it was noted that he had been living in Oregon under an assumed name. That too raised suspicion. Apparently, in the Montana courtroom, circumstantial evidence against Pepo was the next best evidence.

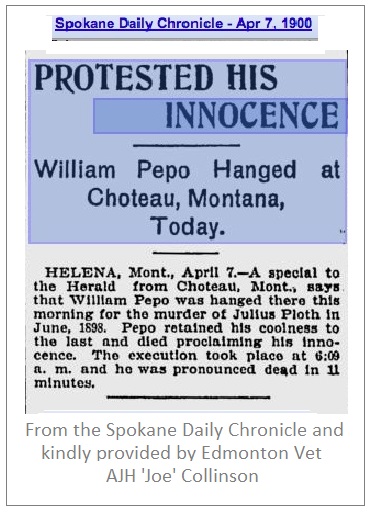

Pepo lost. He was sentenced to hang. He went to the gallows all the while confessing his innocence. But, his last words were of little value. In a few short minutes he was pronounced dead.

It is unlikely that anyone will ever know if Pepo was actually guilty of the murder of his one time friend, but there may be lesson for all of us in 'The Mystery of the Constable Whose Confession Came too Late'. One’s life can be summed up as worthwhile if others know you as a trustful person and in possession of a good, solid reputation. Nevertheless, the whole world knows also how easily just one indiscretion can cause one's reputation to fall torn and tattered.

A person’s reputation is more valuable than all the gold in the world. People develop and nurture their personal and business habits so as to allow other people a sense of trust and worthiness. In court as well, a judge often gives weight to a person’s testimony based partly on the person’s reputation in the community. It is well thus to safe guard it.

There is little doubt that the evidence against former Constable Pepo was circumstantial, but his over arching questionable reputation provided the jury with sufficient cause for a conviction. Essentially everything he said came too late.

Few know that Reg.#1917, former Constable William Pepo lies buried in an unmarked grave in Montana, US. R. I. P.

I wish to thank my good friends, Vet Joe & Aggie Collinson, Edmonton, AB for their help with this short story.

'Maintain Our Memories'

From the Fort,

I have the honour to be, Sir

Your Obedient Servant

J. J. Healy