True and Fascinating Canadian History

The Mystery of A Mountie:

Murder and Abundant Mercy

by J. J. Healy

Words. In the world of law, Canadian judges live a life in isolation after their appointment to the bench, but they are allowed one intimate friend. A dictionary.

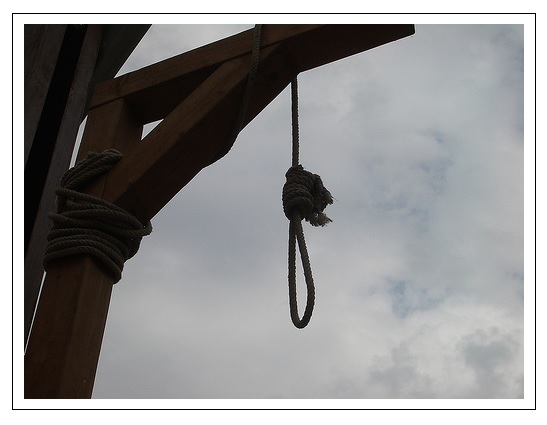

Judicial proceedings in a courtroom resemble a combat zone where a war of words may rage on for days and days among highly trained, clever, and well educated lawyers and the judge. The combat for word supremacy is most apparent and intense if the trial revolves around a murder and much more so if the accused is a celebrity and guilt spells the gallows.

High above the combattants, sits the judge like a Roman Emperor overlooking the fray -- he or she listens with an intense ear to the arguments offered by the adversaries -- opposing opinions are offered during the trial. It falls solely on the judge to untangle words, to sort through their various definitions, as well as to sift through the subtle nuances. In the battle zone, every word spoken by the lawyers may have inferences, naturally in their favour, then thrown like sharp, silver pilums in the direction of the judge.

The battle of legality is exclusively a battle of words. At trial, some words become casualties, while others are raised up as champions. If one word is changed, the law too is changed, and a shift in vocabulary is absolutely crucial as it raises the possibility of an acquittal, and thus the life of the accused will be spared.

In a murder trial, the role of the learned judge, his or her intimacy with words, and the proximity of the dictionary cannot be underestimated.

The story which follows is about an old time murder, but given a fresh face. In the opinion of the police the case was open and shut -- the jail warden had given his word for the gallows, but in the final moments of the trial the judge said something which was a surprise and which no one expected.

The unique conduct of the trial judge and the words he used towards the accused will become apparent in the sad affair titled: The Mystery of the Mountie: A Murder and Abundant Mercy. The murder trial had as many twists and turns as a full blown cyclone sweeping across the Canadian legal landscape. There is a lesson here also for all police officers.

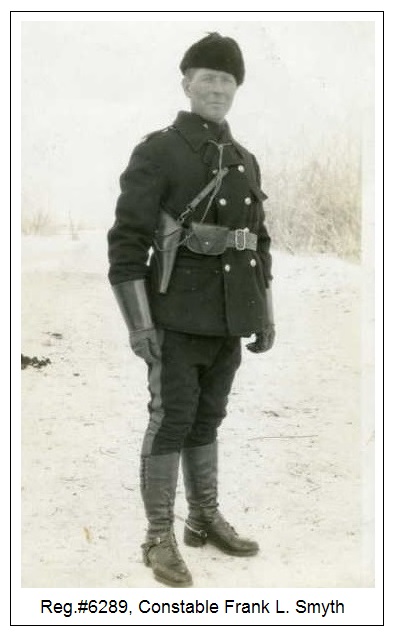

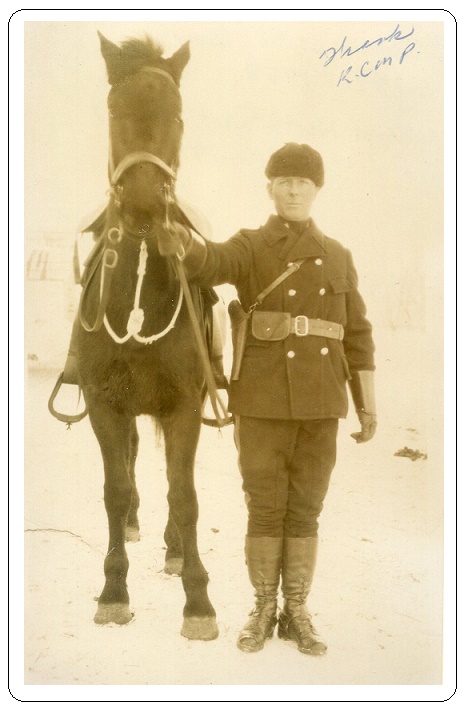

The year 1931 was dismal and lean. Across the breadth of Canada, the Great Depression had tossed one third of Canada’s labour force out of work, and twenty per cent of the country’s population had become dependent on government assistance -- as meagre as it was. Thousands of people criss-crossed Canada on rail cars hoping for work. They sought any kind of work, hoping to feed their family. Frank Leslie Smyth counted himself among the unfortunate and the unemployed.

Smyth was born in LaCrosse, Wisconsin, USA in 1891. He was reputed to be a good and loving husband, deeply devoted to his six children, and a generous and a caring man. He and his wife had been married for fifteen years, and the family including their six children, lived in Grouard, northern Alberta. Like thousands of other men, Smyth was desperate for work but work was impossible to find.

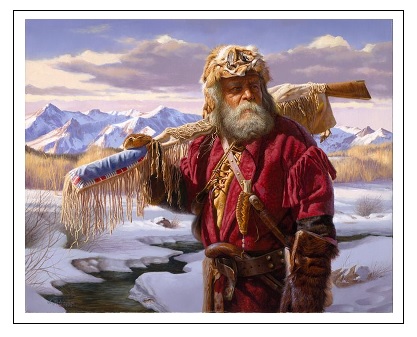

In desperation, Smyth turned to the woods. He worked several trap lines in an effort to snare small animals, sell their pelts and thus buy enough food to feed his family. It was enough to get by. But, life was tough and complicated, and his trap lines necessitated that Smyth be absent from his family for several weeks at a time.

All the while he was away, Smyth nursed a deep, suspicious and disturbing problem in his mind and heart; he was fighting two kinds of predators simultaneously; animals in the woods of northern Alberta, and another animal whom he knew often invaded the intimacy of his home and took to his wife’s bed while he was away. It was no secret that over a ten year period Frederick Lawrence ‘Toots’ Knibb often visited Smyth’s home during Smyth’s absences. The right opportunity had not yet arisen, but Smyth hoped to catch Knibb someday in the midst of the evil relationship. That opportunity presented itself on the early morning of January 31, 1931.

Down through history, murder has always come in different varieties; brother against brother, lover against lover. Sorting out murders was nothing new to RCMP Sergeant A. R. Schutz, or, so he thought. Throughout Alberta, Schutz was known as a crack and experienced criminal investigator, but on this early, dark morning in 1931, as he approached the murder scene inside the Smyth home, Schutz realized that nothing could prepare him for the ugliness and surprise that he was about to face. An hour earlier, rifle shots had been heard from inside Smyth’s home, and as Sergeant Schutz approached the house he had firmly concluded that his life as a police officer was about to change forever.

After entering the house, Sergeant Schutz saw the still warm corpse of ‘Toots’ Knibb on the bedroom floor, and the slightly wounded Mrs Smyth nearby, then his eyes met the murderer face to face -- it was his longtime acquaintance and his friend Frank Leslie Smyth who was sitting placidly on a chair with his rifle nearby. The bedroom smelled of fresh blood, and gunsmoke. Schutz felt in no danger to himself.

At the scene, Sgt. Schutz quickly analyzed the events of the past hour or two. The shooting occurred at 2AM, when Smyth had returned home unexpectedly after several days tending his trap lines. He was armed with his fully loaded hunting rifle, and as he entered his home, he surprised his wife and Knibb in bed. Smyth’s rifle went immediately to his shoulder, and gunfire filled the bedroom. Sgt. Schutz counted five rifle bullet entry marks in Knibb’s body which had rolled off the bed and rested on the bedroom floor. One of Smyth’s rifle bullets had also slightly grazed Mrs Smyth’s leg.

As he had fully expected, the noise of the gunfire awoke the Smyth children from their sleep, and Sergeant Schutz noticed how they cowered behind their mother in the bedroom, now turned into a murder scene. Unable to speak at first due to obvious shock, Edith Smyth the oldest child, eventually blurted to Sgt. Schutz that Knibb was a frequent visitor to her home whenever her father was away. Sometimes, Edith Smyth said, "Knibb would stay for a week."

In spite of his experience as a hardened investigator, Sgt. Schutz knew criminal law and for it, he knew too much. Murder surely meant the gallows for Smyth. Seeing his friend Smyth, Sergeant Schutz’s mind was almost immediately filled with fear and horror; Frank Smyth was a former member of the RCMP and the sole suspect in the murder of Knibb. Smyth made no effort to escape from the law, but instead repeated freely that he had shot Knibb. It’s not what Sergeant Schutz wanted to hear from a friend.

It seemed like an hour had passed by, but it was only minutes that Schutz had been standing in the doorway of Smyth’s bedroom. It was enough time for his mind to wander to a future scene. He knew that he would be expected to witness Smyth’s execution; Sergeant Schutz looked at Frank Smyth and knew what he had to do. He placed Smyth under arrest for murder and escorted him back to the RCMP Detachment. There was no need for more words, there was nothing else for either man to say.

Later at the Detachment, Sergeant Schutz explained the seriousness of Smyth’s free and untimely admissions about the murder of Knibb to The Officer In Charge, RCMP Superintendent A. G. Marsom. Sergeant Schutz had written it all down.

Smyth: “Well, here I am sergeant, you needn’t be afraid. I’m not going to get away.“

Schutz: “Smyth, you’ve been a policeman and you know what this means. He went on and told me all about it. I tried to stop him warning him twice that what he said might be used against him. I told him that he had better keep still.”

Smyth: “I had come home and heard Knibb coughing, with that I kicked in the window, then I let him have it. I pumped about four bullets into him. He started to get up, I took aim and let him have one through the heart.“

A day or two later, Sergeant Schutz was instructed by the court to arrange for witnesses to appear at the murder trial of Frank Smyth. The eldest Smyth girl told the jury, “Knibb said he didn’t care if my father did kill him." Mrs Moore, sister of Mrs Smyth said Frank Smyth came to her home after the murder and he told her, “I’ve killed that darn Knibbs at last.” She also said that, “Knibb's reputation was that he was an idler, and free with women.”

Mr. R. R. Goodwin, a telephone operator took the stand. He said, “Frank Smyth told me what he had done, and he asked me to get the police.” Mr. Goodwin also spoke of Frank Smyth’s good character. Another telephone operator told the jury, “I asked Smyth why he waited so long before killing Knibb, and Smyth said he had never caught him before.” The operator also testified that Smyth had been insistent that the police be called. He praised Smyth’s character highly.

Sergeant Schutz testified before the jury. He repeated the conversation which he had had with Frank Smyth on the early morning of the murder. He said the murder had occurred at 2AM, when Smyth had returned home unexpectedly. He was armed with his fully loaded hunting rifle, and he surprised his wife and Knibb in bed. Smyth fired five bullets into Knibb’s body and one of Smyth’s rifle bullets had slightly grazed Mrs Smyth’s leg.

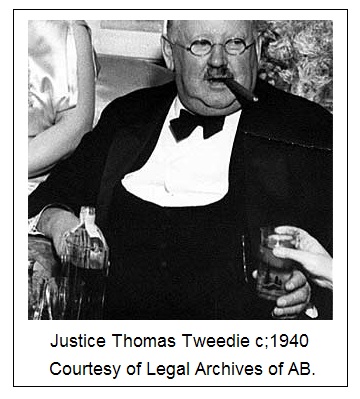

Mr. T. M. Tweedie, Chief Justice of Alberta presided over Frank Smyth's murder trail, and he instructed the jury on the law. Justice Tweedie said, “Now we have come to the last act in this great drama of life that has been played out before you, and before the curtain falls you gentlemen must decide whether the accused who shot in defence of his home and his honour will go down to his death ignominiously on the gallows and then to a nameless grave, or return to the bosom of his family and those far off shores of Great Slave Lake. For the crime which he stands charged is murder, and the only penalty for murder is death.”

“There are several principals in this great drama”, Mr. Tweedie said, “Smyth is the main factor. Then there is Knibb apparently born only to gratify his sensual desire. There is Mrs Smyth apparently false to her marriage and other vows and then there are the children -- six of them -- of whom the accused thinks the world.”

“You, the accused on the night in question, had done what any red-blooded man would have done on finding “a beast” as he termed Knibb in bed with the wife of his bosom, and polluting his children.” The jury heard every precise, deliberate word of Mr. Justice Tweedie. They had no need of the dictionary to distinguish one word said by the judge from another.

The jury adjourned. Three hours after convening, the jury returned to the courtroom. The jury told Justice Tweedie they had decided to reduce the criminal charge of murder to manslaughter. It was a change of one word to another, but as significant a shift in words as an underground volcanic eruption. Vigorous hand clapping broke out in the Edmonton courtroom after Smyth’s reduced charge was announced according to newspaper accounts. Further, the jury recommended to the court, that the judge consider the “utmost leniency” be displayed towards the accused in passing sentence.

Mr. Justice Tweedie then wrapped up the day. He spoke out loud about soul searching matters which other people in the courtroom were thinking.

Mr. Tweedie said, “Frank Smyth, there were extenuating circumstances in your case, but not to such an extent that it would have warranted a verdict based wholly on sentiment. Having regards to your unimpeachable character, your industry, your love of home and family and your forbearance throughout your wife’s relations with Knibb, I am going to give full effect to the jury’s recommendations.”

Taking into consideration the recommendation of the jury, Justice Tweedie told Frank Smyth, “I find you guilty of manslaughter.” The conviction was inevitable. That was justice.

The judge added, “I could sentence you to a long term, and then recommend that it be shortened and use my influence and your good past to obtain parole. But I am not going to do that. I feel that the ends of justice will be fully met in this case by the sentence I am about to impose. I sentence you to six months imprisonment in the Fort Saskatchewan Jail.”

And then Mr. Tweedie said, “The imposition of a six month sentence would be as light as I feel I could mete out." The sentence was compassionate. That was mercy.

With the final words of Mr. Justice Tweedie having been spoken, the most sensational drama in Alberta and the criminal trial of RCMP Constable Frank Leslie Smyth was over. Newspaper reports said that tears rolled down the cheeks of witnesses as they crowded around him. Armed guards allowed Smyth space and time to shake hands with all the members of the jury who had recommended that the "utmost leniency" be extended to him. And then Smyth was whisked away. Sergeant Schutz went back to the Detachment -- it was said that he slept that night for the first time in weeks.

And on that day in Edmonton, AB. the great scales were balanced: on the one side justice and on the other side mercy.

Reg.#6289, Frank Leslie Smyth had joined the RCMP in 1914, and he had served honourably for five years throughout Manitoba and Alberta. His salary in the Force was not enough to properly feed his family, so he turned to a life of trapping and by hunting aminals thus he hoped to gain considerable more for his loved ones.

The story of Frank Leslie Smyth raises a few serious questions which might be asked and add up to the mystery; first, why did it take Frank Smyth so long to settle the score one way or another with Toots Knibb, and second, how did Knibb get away with his evil behaviour for so long? And finally, why did Frank Smyth not confront Knibb in a less violent way and at a place of his preference rather than resort to murder or manslaughter in his home and in front of his children - had he ever thought perhaps of a fist fight, man to man?

The story of Frank Smyth provides all police officers with a small lesson in life, and it has everything to with compassion. First, violence of any kind towards another person can never be endorsed, but instead there are chances in the daily life of every police officer to offer a smile, to say thank you or to show a little compassion to a suspect or the prisoner in the box. One never knows if personal circumstances in our life will place us someday in the docket and in front of a judge. Let us hope that he or she shows some mercy towards us and speaks a kind word or two.

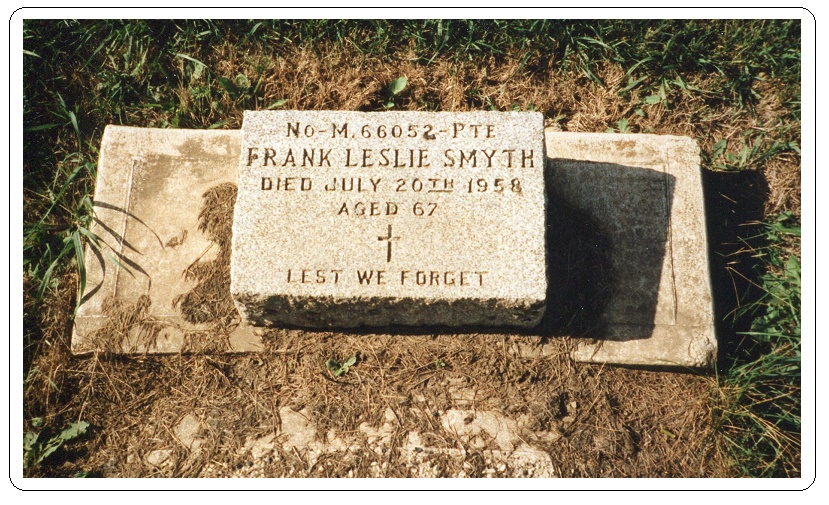

Photos courtesy of Ancestry.ca & Merle Armstrong. Vets London, ON

He was buried in McCue Cemetery, High

Prairie, AB.

His grave was found by Merle Armstrong. Vets London, ON. 2016.

I would like to sincerely thank my friend RCMP Vet Merle Armstrong in London, ON for sending me the newspaper articles about the murder of 'Toots' Knibb by former RCMP Constable Frank Smyth. Merle knew that the story would raise in a few serious questions which would likely add up to a great mystery. Thank you Merle.

The story of Frank Smyth's criminal trial was taken from a few old newspaper articles originally from the Edmonton, AB area, but neither the articles or the authors were identified nor could dates be found on any of them. The print might have been copied from the 1931 Edmonton Journal by Ancestry.ca and if they were, I would like to acknowledge the Edmonton Journal.

Reg.#5561, Sergeant Adam Roman Schutz served in the Force from 1913 to 1938. He died in 1979, and he was buried in White Rock, BC. This story was written in his memory. R. I. P.

Reporting from the Fort,

J. J. Healy

November 11, 2016