True and Fascinating Canadian History

A Mystery of the Mounties:

It's a Sin to Tell a Lie

by J. J. Healy

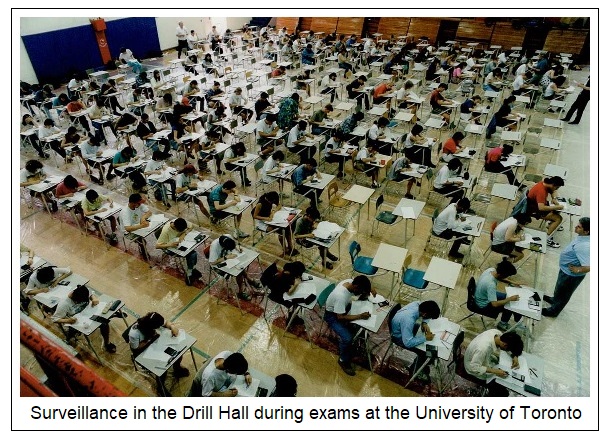

Cheating is never condoned in any aspect of life whether one is in school or connected to business, sports, government or any of the professions. At the University of Toronto, every conceivable precaution is taken to curb cheating during exams; one’s identification is checked and verified, students are escorted to random assigned seating and auditors closely monitor ever stage of the exam process. Active surveillance by professors is designed to eliminate any impropriety in the classroom -- it seems that some students cannot be trusted. If caught, sanctions for cheating can range from a failing grade to expulsion from the university.

But, it’s not cheating in the classroom that concerns people connected to the administration of the law, rather it’s perjury in the courtroom -- recall that the police officer’s edict is that they are expected always to tell the truth.

In a Toronto newspaper article (2012) titled, Police who lie: How officers thwart justice with false testimony, journalists David Bruser and Jesse McLean reported that 100 criminal cases from across Canada were examined where perjury was apparently noted. These statistics are high as well as startling. How a police officer could ever commit perjury or how perjury could get a foothold within Canadian policing is a major mystery by any measurement? There may be a lesson or two for all police officers in the short story which follows entitled: "The Mystery of the Mounties: It's a Sin to Tell a Lie."

Perjury is deliberate lying by a witness in the courtroom while under oath or affirmation. From the time one is a tiny tot, parents and teachers drill into the minds of children that lying is always wrong, that God has a very low tolerance for anyone who purposely lies and that liars will forever suffer the damnation of hell. Children the whole world over know that forever it's a sin to tell a lie.

As a police officer, the consequences of perjury are overwhelming and far reaching; it can result in a miscarriage of justice, it disrupts the search and discovery of the truth in court by the judiciary, it lowers the level of trust which society has of police officers, it ruins one’s reputation, and perjury is a criminal offence.

According to journalists Bruser and McLean, perjury is prevalent among police agencies Canada wide, the RCMP is also mentioned, and they reported that there are few consequences in some jurisdictions for a police officer’s dishonesty on the stand. One can imagine that the newspaper article has forced upper management to review force policies with regards to dishonesty within its ranks, and to be more vigilant in cases where perjury is suspected or reported.

Over the years, and as far as one can tell, the RCMP has been particularly fortunate with only a few incidents of perjury having been recorded among its total membership -- maybe one or two cases a year. However, the few cases that became public did gain wide national attention. In 2007, four members of the RCMP were involved in the taser death of Robert Dziekanski at Vancouver’s International Airport. Following the death of Mr. Dziekanski, a public inquiry was held and an RCMP corporal and three constables presented oral testimony. It was alleged that the RCMP foursome concocted a story which they told to police investigators then lied about the incident later at the public inquiry.

All four RCMP were charged with perjury; eventually, two constables were acquitted but the corporal and one constable were convicted of perjury and sentenced to jail. Although the Supreme Court of Canada agreed to review the case, the Court eventually upheld the corporal’s conviction and the one constable’s conviction.

The Vancouver taser case did nothing to enhance the RCMP’s reputation, and the incident was absolutely tragic all the way around -- the generous use of the taser was described in the press as ‘notorious’ primarily because it shocked the conscious of all Canadians. Everyone expected that the Vancouver RCMP members would tell the truth on the stand -- and no one expected them to dream up a story about the death of Mr. Dziekanski. The whole thing left their reputation in ruins.

In another case, The Globe and Mail (2017) reported that in 2009, a senior RCMP officer was charged for perjury as a result of evidence he gave in court subsequent to a 2006 murder. It too was troubling. Apparently, the RCMP member was the author of a flawed forensic report which was picked apart by other experts and found to be ‘not scientifically sound’. (Vancouver Sun. Bolan: 2011).

The accusation that a police officer would perjure him or herself simply destroys whatever confidence people have in the wheels of justice. After the murder case, sentiments of high professional expectation were voiced about police officers who give testimony. The BC Trial Lawyers Association spokesperson said, “A person accused of a crime hasn’t sworn a duty to uphold the law, whereas police officers have, so there’s a different standard, and that different standard makes sense -- people expect to look at law enforcement for that [honest conduct].“ It makes absolutely no sense for a police officer to lie for any reason, and when a police officer does lie it sacrifices the criminal case, it stuns the court and causes them to lower their eyes in disgust, and perjury deteriorates the overall reputation of the police profession.

In a final case, the Toronto press (2012) reported that racial profiling and police deception were at work and meant to hide an RCMP constable’s misconduct. The constable’s action resulted in the loss of a court case in 100 Mile House, BC., the loss of a prosecution of a drug suspect, and the 57 marijuana plants found in the suspect’s pickup truck.

The RCMP constable testified that he stopped the suspect’s truck because it swerved in its own lane. However, the court noted otherwise; first, the judge said the constable followed the suspect for many kilometres before the alleged swerve, secondly, that the swerve was really a well designed pretext to stop the suspect, and that the constable likely saw the suspect at a gas station earlier in the night then concluded he was Asian and assumed he was involved in organized crime. In the end, the court declared that the RCMP constable was being untruthful with the court. The court’s conclusion was a stinging indictment about the constable’s actions and courtroom testimony. It could have all been avoided with sufficient case preparation, and personal and professional resolve to tell the truth.

Within the context of court business, police officers have a solemn duty to assist the court in its determination of the facts. Essentially, the police officer tells a story about the events of the case and the suspect’s role in the case. The system is adversarial meaning that other witnesses and the constable’s evidence can be questioned and challenged. The result of the adversarial system is that a clearer picture of the real situation evolves. Only when all the facts of the case are clearly laid out can the court weigh the evidence and make a finding. It is to the police officer’s advantage to assist the court by testifying fully and honestly. The police officer's evidence is integral to the whole process.

There may be a lesson or two for all police officers in this short story; first, the burden is heavy upon the police officer to be well prepared for court and to tell the truth. There are several ways in which the police officer can best prepare for court; first, reply on court appointed lawyers and defence lawyers to learn as much as one can about evidence, secondly, prepare for court by reviewing the case in advance with the Crown prosecutor.

Review one’s notes. At first, the police officer will be asked to relate their evidence by pure memory of the case. Only then will the court allow for the police officer to refer to notes. Remember that your notebook might be tendered as evidence during the proceedings. The onus is on the police officer to ensure his or her notes are clear, accurate and sufficiently full.

And finally this valuable advice, lock on to the phrase, “Your Honour, I don’t know." Police officers are not expected to be perfect, and to know all things. If the police officer testifies by saying, “I don’t know” the court will conclude that the police officer lacks the knowledge to honestly answer the question. The response, “I don’t know” often times can save the police officer from guessing at a response, or nudging up against the line close to perjury.

There is no need for a police officer to commit perjury. With good preparation, and some effective hints from the experts including Crown Prosecutors, RCMP members can merge into a comfort zone with the art of giving good evidence. Concentrating on good evidence is one area of policing which is easy to improve with a little effort. Eliminating perjury will eliminate poor criticism from the courts.

The end.

Reporting from the Fort,

J. J. Healy

April 9, 2018

The Globe and Mail. Wendy Stueck. January 11, 2011. Updated March 26, 2017

Police who lie: How officers thwart justice with false testimony. (2012). Thestar.com.

David Bruser and Jesse McLean. Staff Reporters.

Retired RCMP officer faces perjury charge over murder trial testimony. November 1, 2011.

The Vancouver Sun. Kim Bolan. Post Media News.